My Sudani-American LiFE #3: A Tayeb Salih Reading Order (Wad Hamid Cycle)

You really should read all his work.

Marhabteyn, habaabkum!

What can I say about Tayyib Salih that hasn’t already been said? I mean, he’s…a genius. An icon. Sudan’s national author? Without question. One of the greatest Arabic authors of all time? I think so1. The greatest Sudanese author ever? Possibly! He’s funny, sensitive, nostalgic, relentlessly critical, well-read, mystical, philosophical, nihilistic…

I just love him. You see, when I was a teenager, I got into classic literature around my sophomore year thanks to my Honors English class. It was my first time encountering capital “L” Literature, and like the most insufferable kid you know: I loved it. I quickly went from reading a portion of A Tale of Two Cities in class to diving into Thackeray and Dickens in my free time, going through “Great American Novels” lists and reading books like Blood Meridian, The Great Gatsby, and Catcher in the Rye. I don’t know if I can put into words what I felt reading those books and I why I enjoyed it so much…

Ah, damn. Anyways. I got curious, naturally, about Sudanese literature, too, and so I looked what the internet had to recommend me: Season of Migration to the North. My Arabic sucked, and I couldn’t get past the first page of that crunchy PDF. I discussed the experience with my dad, who suggested that I read his favorite Tayyib Salih work, instead: The Wedding of Zeyn.

And so I did the unthinkable. I read my first Arabic-language novel, writing down and Google Translating every word I didn’t know, and after God-knows-how-long, I made it through that long trek of 112 pages of The Wedding of Zeyn and I loved it. I decided to go back and read Season of Migration, and found I’d never been so shocked reading a book in my goddamn life. Violence, sex, existential crises…I didn’t know Sudanese people talked about these things, since my main frame of reference for Sudanis was the conservative mosque-going community in my little Idaho town. Since that first encounter with at-Tayyib Salih, I’ve returned to The Wedding of Zeyn, again and again, year after year. I ended up reading Domat wad Haamid, his famed short story collection, and falling in love. being increasingly baffled and saddened by the fact that Season of Migration seemed to be the only thing English-speakers wanna talk about when it comes to him.

But then, this January, I opened up Season of Migration again, for the first time in nearly a decade…in December, I was in Egypt visiting my displaced family, rereading The Wedding of Zeyn for the fifth time or something, when I’d decided to dedicate 2025 to reading all of at-Tayyib Salih’s books with a couple of my favorite cousins. And the first item on that list, after my beloved Zeyn, was Season.

And I got what made the book so goddamn special.

Now, I’ve read all his works under what critic Wail S. Hassan calls “The Wad Hamid Cycle” (this isn’t to endorse everything he says regarding this framing, I think he’s really off in a lot of ways). And I’m in love. And I want to share that love by giving a nice, spoiler free (but hopefully still informative) recommended reading order to maximize one’s enjoyment with Tayyib Salih. Because the truth is: he’s a difficult author. His books are very…novel-y, they’re rich in beautiful descriptive writing, long internal monologues, dramatized scenes of mundane social interactions, and light on pronounced, visual scenes and linear plot. Also, if you’re a Sudanese person, he comes from a generation that’s basically alien to us: one before the modern Sudanese religious revival, so he’s substantially less conservative than the average Sudani in the diaspora today, unabashed in how he approaches taboo topics in ways that frankly still give me secondhand embarrassment. But, I think, with the proper preparation, his Wad Hamid Cycle is one of the greatest reads you could ever get your hands on, and so that’s what this is for.

First: what’s the Wad Hamid cycle?

One of the noted features of at-Tayyib Salih’s fictional writing from very early on was the recurrence of a fictional Sudanese village, Wad Hamid, in each one, with a shared cast of characters. My first thought when encountering this across Season and Domat wad Hamid was the MCU, and I think that’s an apt modern comparison: you have characters who appear in some books, characters who appear in all the books, and the characters’ importance in each individual installment varies from being background, to supporting, to main.

In at-Tayyib Salih Speaks, Ustaz at-Tayyib says that his inspiration behind this was The Odyssey, and the recurrence of characters between Homeric epics: he says he wanted to make rural Sudanese characters legendary, larger than life, mythic personalities.

Whether he succeeded in this or not is an open question. Regardless, what’s important to know is that Wad Hamid (and the stories in it) represents the agricultural, riverine Sudanese Arab village that, for most Sudanese people, represents the essence of the Sudanese past, identity, and cultural values. This village is defined by:

devout, communal, Sufi-influenced Islamic faith that nonetheless manifests in a wide range in religiosity (as in, there are people in at-Tayyib Salih’s works who pray all the time, and people who drink and never pray, but all of them consider themselves Muslim, participate in Muslim community activities, and interact with traditional Muslim authorities)

an ethical system that values humility, tolerance, generosity, contentment, and sociability, but also obedience to traditional hierarchy (especially patriarchal) and family ties

A shared agrarian identity that distinguishes them from their nomadic Arab neighbors

A connection with the land, particularly palm trees, that is portrayed as being gradually eroded by the post-colonial forces of modernization

At-Tayyib’s portrait of Wad Hamid is nuanced and changes from book to book and story to story. In addition with the setting and some characters, the Wad Hamid Cycle also shares a variety of themes, including:

tensions between traditional patriarchs and post-colonial Sudanese educated class

the grandfather-grandson bond

a sense of loss over a bygone romantic past

uncertainty and pessimism about the Sudanese future

oppression of women via the institution of marriage

the connection between Islamic mysticism and love for the oppressed and impoverished

Long-standing friendships among elderly Sudanese

Wail Hassan also seems to be convinced that most of these works share a single narrator, but I’m personally agnostic on this question: I don’t see the textual evidence for it, nor at-Tayyib’s own comments.

Anyways, with that out of the way, I say…

Start with The Wedding of Zein

(this cover is by my favorite Sudanese painter, Ibrahim el-Salahi. You should really check out his work!!)

This, as far as I can tell, is his best-loved work within Sudan, which makes it all the more crazy that it was his first book. It was fully published in 1966 (although it started being published in 1962), and I think it could be arguably described as a romantic-comedy…or maybe just comedy. Anyways, it’s basically about this dude named Zeyn, who’s the village idiot (and very neurodivergent-coded, I don’t know whether at-Tayyib intended this, or was rather trying to represent the archetype of the Sufi holy fool), the news of whose marriage shocks everyone (including the reader). The driving question behind the book, I feel, on the first read, is this: how did this guy, of all people, get married?

In showing us the answer to this question, at-Tayyib Salih takes us on a tour of all the different sectors of Wad Hamid society, how their lives overlap with one another, their bonds and their tensions, discussing everything from wealthy to poor to deaf women, to freed slaves, the deeply pragmatic landowning men of the Village Committee, and the mysterious mystics like al-Haneen. It’s funny, it’s emotional, and it’s a really quick read that I think is probably one of the most Sudanese books ever written. Of course, it is just one kind of Sudani-ness — the aforementioned Arab peasant life along the Nile — but, it is a Sudani-ness I relate to. I read it, and I see my village come to life, and I think the book has this same effect on a lot of people.

If you can read it in Arabic, read. It. In. Arabic. It is one of at-Tayyib Salih’s many books that’s written with Modern Standard Arabic/Fus7a narration, but uses Sudanese Arabic (specifically, his Shimaaliya-grandpa Sudanese Arabic) for the dialogue, and it gives everything a liveliness, informality, and humor that I think isn’t captured in the stilted and formal English translation. Generally, I don’t like at-Tayyib Salih translations: his language is one of the draws of his writing. His prose is just so gorgeous, and I don’t think English translators can manage to capture that space in between theatrical formality and street-casual-speech that at-Tayyib’s writing exists in.

Regardless, though, it’s the best place to start, because it’s inoffensive, not very deep, easy to follow in plot terms, lighthearted, and, again, probably his most popular book in Sudan. It introduces you to many of the people who factor in the Wad Hamid cycle later and it’s a great glimpse into Sudanese life. I think it’s neglected by English writers because it’s not as philosophical as Season, but I still think in terms of narrative structure and themes there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on here that — since it doesn’t fall into the postcolonial paradigms bougie academics love to study — gets overlooked. So read it!

This is notably, also, the first of only two stories in the Wad Hamid cycle to receive film adaptations. And the movie is…meh. A Sudanese cinematic classic for sure, but it too lacks the life, humor, nuance, beauty, and emotion of the original. Sometimes I wonder if it could ever be remade better, perhaps as a miniseries or animated movie, but I honestly think it’s an experience that’s uniquely-suited to reading (and in Arabic. Can’t stress that enough on this book.) Watch this after the book to get a glimpse at the history of Sudani cinema.

Then read: The Doum Tree of Wad Hamid and Other Stories

(I find this old cover very interesting. Almost looks like the tree in the Lorax.)

This is technically Tayyib Salih’s real first book, made up of a series of short stories dealing either with life in Wad Hamid (in particular the incredible trio of A Palm Tree on a Stream, A Handful of Dates, and of course the titular Doum Tree) or encounters between Sudanese people and Westerners (like Suzanne and ‘Ali and So It Was, Gentlemen). At-Tayyib Salih lived in London, you see, so it makes sense a lot of his stories focused on the type of dynamics that manifest between Sudanese people and those who would’ve been their colonizers less than a decade before these stories were written.

Since it’s a collection, the quality between stories varies. I’ll just say that generally, I like all the stories about Wad Hamid, and don’t really care for any of the stories with white people except for Yours Until Death, which is a great love story. The three I listed earlier in particular are extremely moving stories of the tensions between peasant nostalgia and postcolonial modernization, particularly the question of connection with the land and nature, that are easily some of the best short stories ever written.

Via Handful of Dates, it’s also the second Tayyib Salih story to get an adaptation, and the adaptation is…okay. Lovely cinematography, but I don’t think any of the rich internal drama that drives the short story really comes across in the short film. Watching it, I came to conclude at-Tayyib Salih’s stories, as visual as they can be, are probably impossible to adapt for the screen.

This is the best second work, I think, because it builds on the setting you get fully laid out in The Wedding of Zeyn, and if you like The Wedding of Zeyn, you’ll probably like the Wad Hamid stories in this collection. Doum Tree in particular is the most philosophical of Tayyib’s short stories, and it really represents what he later became in terms of how contemplative his writing can be.

Reading this second also gives you an opportunity to decide: do you like at-Tayyib best when he’s writing about Sudanese life in Sudan, or Sudanese life in England? If it’s the former, I would say skip the next item on this list and come back to it after the fourth (especially if you’re not big on sex and violence in your reading time). If it’s the latter, well, then this book is for you…

Alright, yes, you should definitely read Season of Migration to the North

(love this cover, even if the apple image is fundamentally meaningless. This is the copy I have, having gotten it in Sudan in about 2017.)

This is the one book of at-Tayyib’s that gets significant non-Sudani attention, probably because it’s about themes that are more…global in nature: the relationship between the new postcolonial bourgeoisie and their former colonizers. Told from the perspective of an unnamed narrator who is also one of Tayyib Salih’s best characters, Season of Migration is one of the most beautifully written books ever, being at-Tayyib’s only book to be entirely in MSA. It’s part Othello but more psychological horror, part Heart of Darkness but flipped; part Great Gatsby, part Frantz Fanon, part Freud, and all seriously uncomfortable to read — but impossible to forget and turn away from. The book is heavy on the use of sexual violence as a metaphor for the colonization (metaphorical “rape”) of African and Arab lands, which, for a modern reader like me, with a relatively conservative Sudani upbringing, can find really awkward and distasteful with an undertone of objectification (even though, in the book, at-Tayyib is openly sympathetic to the plight of women in patriarchal societies). That said, don’t let that knowledge define how you read the book: to many people try to read Season as a straightforward allegory, with characters representing particular countries or historical moments, which at-Tayyib himself considered a mistake, considering the symbolism in his books to be dynamic and indefinite. I think the best way to read it, having discovered this my second time, is as the increasing mental breakdown of the narrator as his encounter with a mysterious dude named Mustafa Sa’eed forces him to question everything his life is built upon. The book interweaves the story of the narrator returning to Sudan after his education in England, with the story of Mustafa Sa’eed’s rise in the British Isles. It’s filled with cynicism about the African-Arab postcolonial reality and the loss of the miraculous Sudanese rural utopia found in The Wedding of Zeyn and Wad Hamid, where colonial violence seems to have fundamentally warped the Sudanese psyche.

It’s a dense read that yields itself to note-taking and discussion, and thankfully, there’s plenty of discussion of it. I really recommend Leila Aboulela’s discussion of it (available on Spotify), as well as the Bulaq podcast’s discussion. While I was thoroughly underwhelmed by it the first time, viewing it as lacking in plot focus and unnecessarily lurid, I’ve come to appreciate its nonlinear, dream-like structure, with the rich internal monologues being the glue that really holds each scene together.

It also has one of the best and most gripping endings in any book I’ve ever read. It really deserves the acclaim it gets, honestly. Truly. But, like, at-Tayyib Salih’s other work is important, too, so don’t. Stop. Here.

It’s also received a stage play. It’s kind of surprising it’s never got a movie, but I think that’s for the best.

For the love of God, read Bandarshah

Once in an interview, at-Tayyib Salih was asked if he was a writer with only one really great work, that being Season, a critical darling in both the English and Arabic academies. Ustaz at-Tayyib was offended. He said, to understand an author, you gotta read everything they write. And for him, of everything he wrote, he thought his Bandarshah duology was the best and most important.

(the interview, btw)

Bandarshah is a duology of books that at-Tayyib originally wanted to be a series of five, and goddamn I wish he’d finished it. Publishing its second part in 1976, at-Tayyib described the series like archaeological work, saying he only discovered the importance of the series while writing it.

It’s at-Tayyib’s most neglected work by critics, although in Sudan I do see people mention its second part, Maryoud, here and there. In some ways, it’s his most difficult work: here, at-Tayyib is at his most nonlinear and dreamlike, but don’t be fooled by the Orientalizing reviews like Kirkus’s which boil the book down to some impenetrable work of folk Muslim mysticism. Bandarshah is a deeply political work embedded with subtle and nuanced criticisms of the Sudanese political reality in the Nimeiry-era, covering themes of revolution and corruption as the tension between Wad Hamid’s old and young generations comes to a head, with the old — and with it, at-Tayyib’s romantic peasant Sudan — slowly giving in to the vicissitudes of time. It’s filled with ruminations on death, love, God, oppression, family, patriarchy, masculinity, told over the series of anecdotes on Wad Hamid life (somewhat like The Wedding of Zeyn) that are not bound by any particular plot motion. As a result, it’s difficult to summarize, other than saying it’s a series about generational shift, primarily from the perspective of the elderly. The books aren’t lighthearted like The Wedding of Zeyn (although they do have humorous moments), and while violence does feature, it’s nowhere near on the level of Season. That said, I had no trouble binge-reading them, because, despite how utterly mystifying and incomprehensible they can be at times, they’re so gorgeously written, rich in symbolism, and ripe for contemplation and discussion. If only people would.

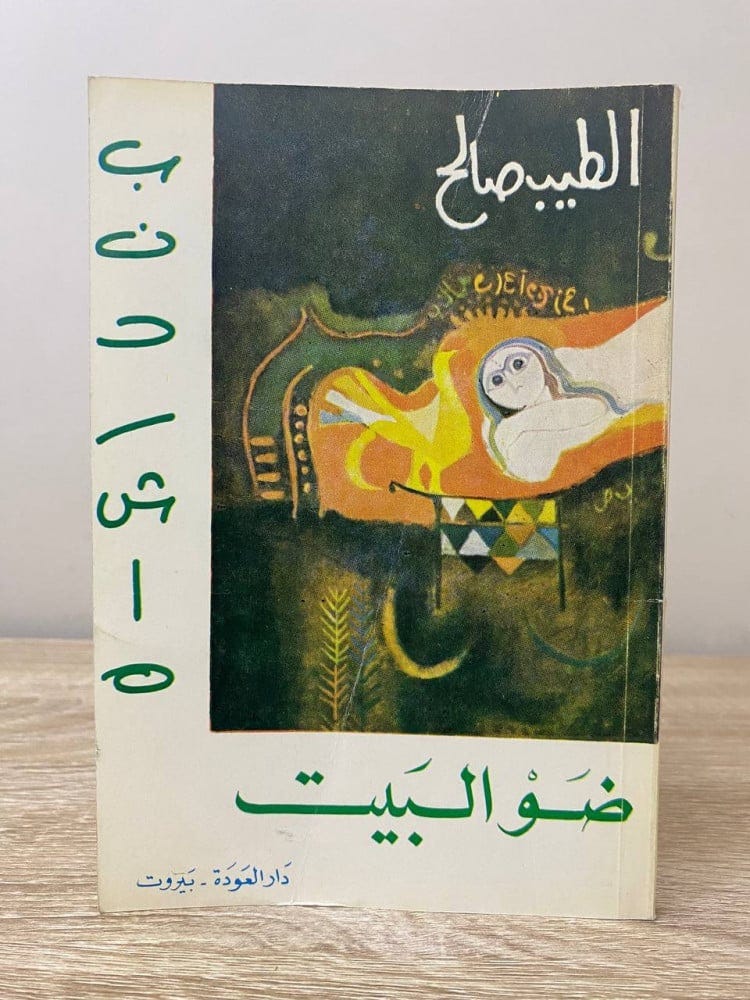

It starts with Daw al-Beyt…

…which, for whatever reason, isn’t mentioned as much as its sequel, but don’t let that let you forget this book. I can’t decide if I like it more than Maryoud — they’re really one book — but it’s definitely an incredible read. I honestly may like it more. It deals with the life of a guy named Miheymid, who tried city life, but has decided to come back in his old age and be a farmer in his hometown of Wad Hamid (Wail is convinced that he’s the same narrator as Season, which I could see, but also isn’t explicit and may contradict some things in Season). Of course, Wad Hamid isn’t what it used to be, and it’s both rewarding and saddening to see how the lives of the characters we’ve gotten to know throughout the Wad Hamid Cycle change in this book. I really don’t wanna spoil anything, so I can stop the synopsis there, but lemme say that it’s probably at-Tayyib’s most complex book, while also being one of his most confusing because of just how nonlinear its structure is.

I think it’d make a bad movie, but that makes it an even better read: it’s a book that’s especially immersed in the unique tools of its format.

…and it ends with Maryoud.

The shortest book of the Wad Hamid cycle, but easily one of the most poetic, memorable, emotional, and satisfying. It’s tighter structurally than its predecessor, really zeroing in on the story of Miheymid (who’s one of my favorite characters in literature, especially if he is indeed the same kid from Handful of Dates and narrator from Season of Migration) and his extremely moving, beautifully written, and tragic relationship with his childhood love. It also features more ruminations on the mysterious legendary figure of Bandarshah, an archetype of tyrannical worldly authority who is varyingly imagined to be Ethiopian, Nubian, or European…but always powerful, embodying a critique of both traditional Sudanese patriarchal authority and potentially modern Sudanese political authority as well. Would love to discuss it more, but really can’t spoil.

It also features a beautiful chapter on at-Tahir wad ar-Rawwasi that is a lovely development of this recurring background character, maybe being the most explicit expression of at-Tayyib’s narratives championing the cause of the poor and subjugated in Sudanese society.

Unfortunately, Maryoud never got the sequels Ustaz at-Tayyib wanted for it, so we’ll never know if the next three Bandarshah novels would’ve cleared things up, tied them together, or built on the loose ends present in both Bandarshah books. You can criticize Bandarshah as an incomplete or overly ambiguous work, but as time goes on, I find myself appreciating its refusal to provide certainty more and more. Indeed, uncertainty is the state that governs the living characters in the story: at-Tayyib denies us the catharsis he provides the reader in The Wedding of Zeyn, perhaps fittingly, for the reality that would come to unfold for the country these characters represent.

Okay, and there’s also “The Cypriot Man”

Which is undoubtedly an episode of Bandarshah, a short story he published between the two books, and it’s…fine. It’s interesting, really, because of the Bandarshah style present in it, but I don’t think it manages to be as interesting or powerful as the novels in the series. It’s also more sex-as-metaphor stuff, with it being less effective here, I think, than Season. But you should read, decide for yourself.

Then, there’s a whole lot of other stuff

After Maryoud, at-Tayyib Salih, for unknown reasons, abandoned writing fiction in favor of literary journalism, with his articles getting published in tons of collections in the 21st-century. This includes everything from at-Tayyib’s memoirs, to literary criticism of al-Mutanabbi and other classic Arabic poets (who at-Tayyib really loved), to the only one of at-Tayyib’s nonfiction works to get an English translation: Mansi, A Rare Man in His Own Way, written about at-Tayyib’s extremely eccentric Egyptian friend.

(at-Tayyib and the friend he mined for satirical writing content)

There’s also one short story he wrote outside of the Wad Hamid Cycle, “A Blessed Day on the Banks of Umm Bab,” a story he wrote at the request of a Pan-Arab literary project, and his only story to not be in Sudan or about Sudanese people. Haven’t read it yet, but, I’ll definitely say, I’m glad I read the Wad Hamid Cycle first. As I explore Sudanese literature throughout this year, I very much doubt I’ll find any book, Sudanese or otherwise, that matches up to the utter masterpiece the Genius of Arabic Novel-writing put together at the beginning of his career.

الله يرحم الطيب صالح ويغفر له

يا عبقرينا العظيم

I’ve only read at-Tayyib Salih, Ghassan Kanafani, and part of a Ghada as-Samman book, please don’t take this opinion seriously.