My Sudani-American LiFE #10: Tayeb Salih's "Bandarshah" Duology (1971-76)

Review of an under-discussed classic. Spoilers ahead!

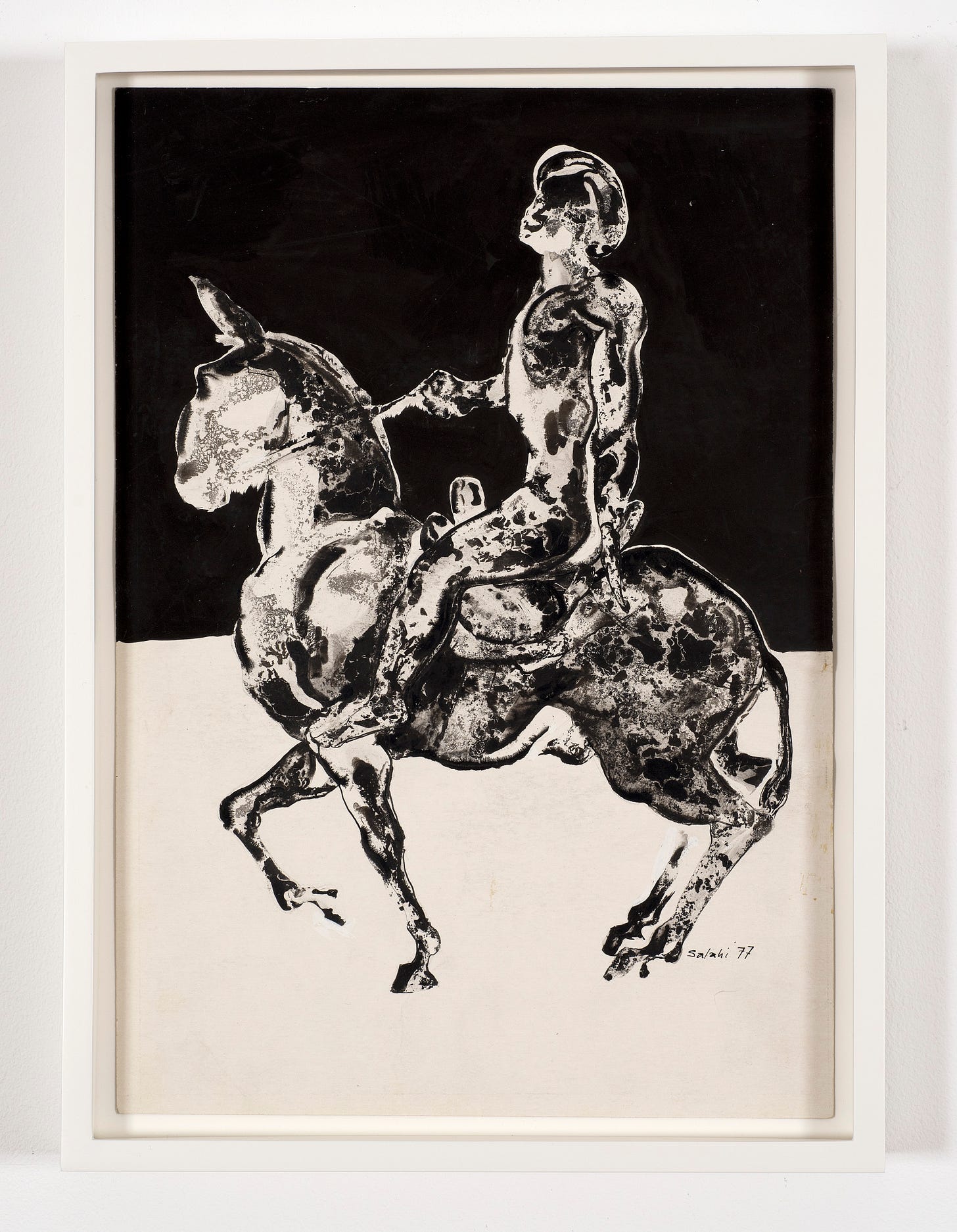

(a drawing, probably of the Bandarshah, by Ibrahim el-Salahi)

While rereading my favorite book, The Wedding of Zein, in Egypt last December, I decided to dedicate 2025 to reading at least one Sudanese book a month, with a focus on those who seem to me the most influential voices in Sudanese literature: Tayeb Salih, Hammour Ziada, Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin, Abdalla Eltayeb, Leila Aboulela, and Safia Elhillo.

It's been a blast so far—I’ve read five books, starting with all of Tayeb Salih's fictional works, both short story and novel. I began by treading familiar ground (The Wedding of Zein, Season of Migration to the North), but eventually decided it was time, after nearly a decade of reading the same few books, to step outside my Sudanese literature comfort zone. One trip to the University of Arizona library and a few clicks on Amazon later, I got my hands on physical copies of Tayeb’s least appreciated work: the Bandarshah duology (Dau el-Beit and Maryoud).

The Overlooked Masterpiece

Tayeb Salih stated multiple times that Dau al-Beit and Meryoud, collectively, formed his best novel. He even hoped to follow them with three additional installments that sadly never materialized.

Among Sudanese readers, Bandarshah seems far less popular than The Wedding of Zein, Season of Migration, and The Doum Tree of Wad Hamid. I suspect this is because Tayeb Salih is often seen as a culture writer and author of collective nostalgia; the more beloved works are either romantic representations of rural riverine life or lamentations on the loss of a peasant past. I find Wedding and Doum especially well-liked, probably for their more positive depictions, whereas Season is darker—violent and sexual in a way that tends not to resonate, especially with more conservative Sudanese. I do hear Meryoud mentioned now and then, but overall, neither entry in the Bandarshah series seems to enjoy wide readership.

Then, among Western readers, Season is really the only work of Tayeb’s they deeply engage with. Bandarshah was translated into English, but that version is now out of print. Reflecting a broader ignorance of Sudan’s social realities, early Western reviewers like Kirkus found it “too stately and mystical.” Wail S. Hassan, for instance, attempted to frame the novel within Arab nationalist thought, missing many of the text's more localized messages. There’s a great article called “Speculative epistemologies of resistance” that breaks down the Western academic response to Bandarshah and why those readers have generally missed the point, though it still leans heavily on a broad postcolonial framework that doesn’t fully capture the local specificity of the text’s themes.

Complexity and Generational Change

To be fair, Sudanese or not, I think it’s hard to dispute that Bandarshah is Tayeb's most difficult novel. At its core, it reads as a series of vignettes centered on generational change and modernization in Sudan. It feels like a grand payoff to the themes and characters of Tayeb’s earlier work: all previously-mentioned residents of Wad Hamid return, and the recurring themes of education, modernization, and the erosion of traditional values in riverine Sudan resurface.

Bandarshah, like The Wedding of Zein, is set entirely in Wad Hamid. But unlike Wedding, which is celebratory, Bandarshah carries a tone of tragedy—pessimism about the future, portrayals of social decay, and a kind of grim antimaterialism. Something I find really interesting in the context of post-2018 Sudanese nationalism is that Tayeb’s idyllic Sudanese past isn't one of ancient kingdoms at the peak of sovereignty and regional influence, but of values associated with rural (and thus “traditional”) Sudan: connection to the land, endurance, social hierarchy, collective interest, generosity, and disinterest in worldly wealth or power.

The Myth of the Bandarshah

This themes are best exemplified in the vignette from the first book about Dau el-Beit, a man with no memory of his name, religion, or homeland, who is adopted by the people of Wad Hamid. He is implied to be an Ottoman client, which, fascinatingly, I think, makes this story one of colonial encounter. However, it’s a stark contrast to the violent portrayal of European colonial encounter in Season. While Salih never has a Things Fall Apart moment where he portrays the introduction of English colonialism in Sudan, he alludes to an infamous incident in which colonial general Kitchener admonishes a local Sudanese leader before their execution by telling them “why have you come to my country to cause chaos?” The violent characterization of the colonial encounter ultimately shapes the psyche of Mustafa Sa’eed on an instinctual level, who marries a British woman, then murders her, reversing the violence inflicted by the colonialist.

Bandarshah diverges significantly by instead concluding the encounter with a peaceful triumph of Sudanese ethical ideals. The stranger is given a name, land, and a life by the locals; he learns to farm, converts to Islam and marries a local woman. There is no violent battle, like what defines the Sudanese-British marriage in Season. Rather than death, the Ottoman-Sudanese union instead gives life to Isa, a boy with his mother’s dark skin and his father’s green eyes. Isa earns the Persianized nickname "Bandarshah": king of the city.

This is where the archetypal myth starts to be revealed to the reader. Tayeb’s novels often hinge on a central event—Wedding has the wedding; Season has the murder of Jean Morris. In Bandarshah, the central event is a myth: a foreign ruler who violently takes over Wad Hamid, hosts decadent banquets, and watches with his right-hand man as eleven subordinates are whipped before they eventually rise up and kill him.

The myth appears in multiple forms: the Bandarshah is variously a pagan Nubian, a Christian Ethiopian, a Muslim, a European—but the story remains the same. In Dau el-Beit, Isa takes on this role, appearing in fine clothes among poor children, who then give him the nickname. In dreams experienced by multiple villagers, he and his grandson Meryoud oversee the whipping of Isa’s eleven sons, including Meryoud’s father—who later kill them in real life by returning the favor.

Revolution and Modernization

The Bandarshah myth deserves its own essay, but it is a mistake to focus solely on the central event in a Tayeb Salih story. Part of what draws me to the duology is how it portrays the evolution of Wad Hamid’s characters, within the framework of generational struggle, as material and social authority begins to change hands. Dau el-Beit in particular has this fascinating development of at-Tireyfi, the rambunctious child from The Wedding of Zein, who leads a revolution against the old men of the village committee—men who held power due to age, land, and embodiment of traditional masculine ideals.

This revolution mirrors real political developments in Sudan, especially the 1964 uprising that removed Abboud’s military regime and ushered in a government of educated urban elites. Across Sudan, similar shifts have been playing out since the colonial era at the very least: younger, city-educated Sudanese sought modernization, replacing an aging generation rooted in different values.

Bandarshah romanticizes the elders’ stories, but the younger generation—especially Miheymid, who narrates portions of the text—is filled with cynicism and anxiety. Despite their aspirations, they can’t fully realize the technological and ethical advances they desire. Instead, they’re left watching the loss of social bonds and beloved traditions, and yearning for justice.

This culminates in the vision of Sa’eed ‘Asha al-Baytat, who has a dramatic and wondrous dream in which he resists seduction by Bandarshah wad Dau el-Beit’s women, angering Meryoud, and asserting his own identity before leading an otherworldly call to prayer. Despite his poverty and fragility, he proclaims himself "the Bandarshah of [his] time." The dream, like much of the novel, portrays a hope for triumph by the present over both a past of violent authoritarianism and a future of cynical materialism. That said, it never gives us the satisfaction of showing us how this victory can truly be actualized.

Prose & Scripture

What makes Bandarshah so powerful is not just its themes, but its language. Tayeb weaves MSA and Sudanese Arabic together with so beautifully, with characteristically vivid descriptions of nature and body, along with natural, onomatopoeic dialogue, strewn with deep Quranic references. The ending of Meryoud is especially characteristic of this: Miheymid dreams of crossing the Nile, just as he did as a child, but now as an adult. He’s trying reach Maryam, his recently-deceased childhood love who he buried with his own hands. Echoing the Qur’anic tale of al-Khidr and Musa, Maryam refuses Miheymid’s request to go with her, telling him that he will not be able to be patient with her. The allusion is profound: the story of al-Khidr is typically interpreted as a story about the divine wisdom behind suffering, and how it confounds humans. Miheymid’s response to Maryam’s chastisement perfectly embodies this: he is bewildered like Musa in the Qur’anic tale, ending the novel by saying he wished to turn back, but had forgotten the way. The novel ends with him lost between worlds, unable to return—suspended between life and death, past and future, just like the chilling finale of Season of Migration.

Humor, Humanity, and Heart

Amid the myths and revolutions, Tayeb still gives us charming, often comedic vignettes of village life. Three that stood out to me: wad ar-Rawwaasi’s rivalry with Nile fish, his father Bilaal’s backstory, and wad Haleema’s unforgettable butaan tale. These stories are lighthearted, but never feel superfluous meaningful, showing the village world that draws so many to Tayeb’s fiction, and establishing the grounds for the romantic nostalgia that defines the duology’s vision of the past.

One Book or Two?

Is it fair to talk about Dau el-Beit and Meryoud as a single novel? Perhaps not. Each has a unique arc and tone. Dau el-Beit is more social and grounded; Meryoud is more internal, pleasingly blurring the lines between myth and reality with a magical realist approach that Tayeb always emphasized as characteristically Sudanese. I can't choose a favorite between the two—Meryoud is probably Tayeb Salih’s most gorgeously written book aside from Season, maybe, but Dau el-Beit is equally strong in its insight and narrative force.

Final Thoughts

I plan to reread Bandarshah and write more about it, inshallah. Even on a first read, though, it feels like a strong contender for Tayeb Salih’s masterpiece—philosophically rich, stylistically mature, and emotionally and thematically complex. It resists the cultural and postcolonial binaries often projected onto his work.

It’s a classic of Sudanese and Arabic literature, and probably my second favorite Tayeb Salih work—just behind The Wedding of Zein for the sheer joy of the reading experience. Despite my preference, though, it’s Bandarshah's complexity, ambiguity, emotional weight and indeed its difficulty that make me appreciate it. It demands a lot from the reader, encouraging deep contemplation of the Sudanese present.

How about you, what did you think of the book? If there’s one thing this classic deserves, it’s to be talked about more.